Chapter 1

In the Beginning

Approximately 13.8 billion years ago, the Universe we know was born out of the Big Bang. The Earth formed from the coalescing debris just over nine billion years later, and a mere 300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens emerged on the scene.

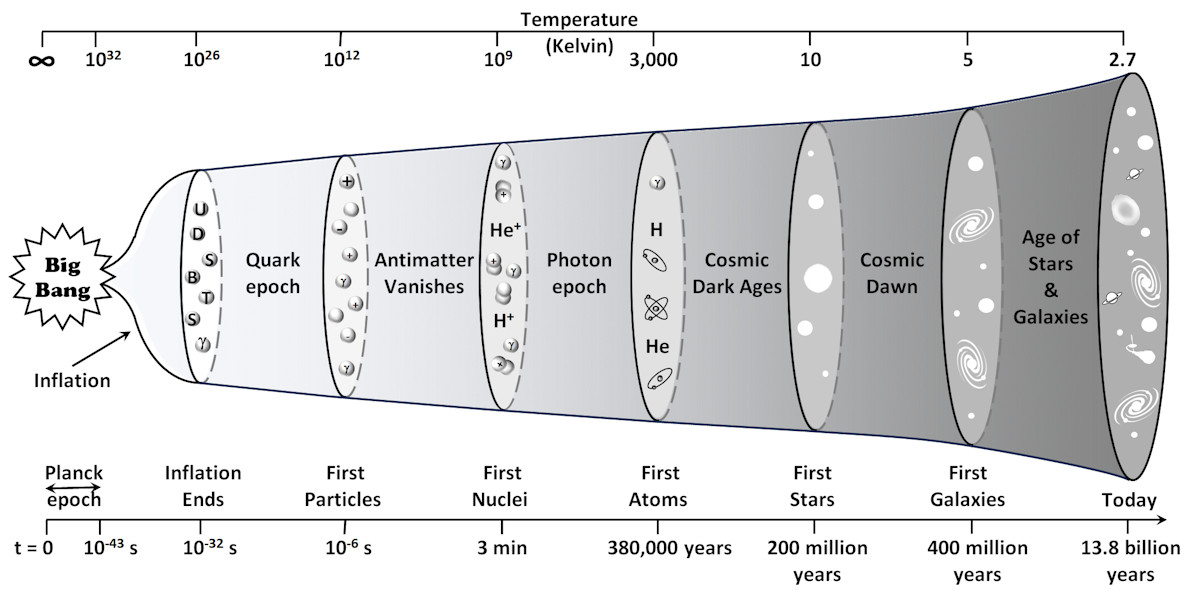

In the beginning, there was nothing – no space, no time, nothing. And God said, "Let there be light", and there was light – an infinitely hot, dense speck of pure energy. No one knows how this speck came to exist out of nothing. The Big Bang theory only tells us how the Universe evolved, not how it began. The first ten-billionth of a trillionth of a billionth of a second (10⁻43s) after the Universe began, a period known as the Planck epoch, is a mystery. Everything we know about the Universe relates to the time after the Planck epoch.

The instant of the Big Bang created every piece of matter and energy in the Universe today. No one has added anything since, and nothing has been removed. Colliding particles may annihilate each other, but the resulting energy persists. This energy can later transform into new matter, demonstrating the principle behind Einstein's famous equation, E = mc2, which shows that mass (m) and energy (E) are interchangeable, and this is how energy from the Big Bang created the material that would ultimately build our Universe.

The Universe's initial expansion was incredibly rapid. During a brief moment called the inflationary epoch, it expanded at an extraordinary, trans-warp speed before decelerating to a much slower rate. While nothing can travel through space faster than the speed of light, space itself can expand at a rate that surpasses this limit – precisely what occurred during inflation. In an astonishingly short time (10⁻32 seconds), the Universe grew by a factor of at least 10⁷⁸, all in the blink of an eye. This rapid expansion helps explain why the Universe appears so uniform in all directions and resolves several cosmological puzzles.

As the Universe expanded, it cooled. One-millionth of a second after the Big Bang, the temperature exceeded a trillion degrees Kelvin, and the Universe was incredibly dense – four trillion times denser than water. By then, it was the size of our solar system and had cooled sufficiently for quarks, photons (particles of light), and electrons to form. Different flavours [1] of quarks then merged to form protons and neutrons, and within a few minutes, some of the newly formed protons and neutrons combined further to form helium nuclei. The Universe was awash with hydrogen nuclei (protons), helium nuclei, and free electrons. Yet, it was only a few minutes old.

Within the initial millionth of a second, the four fundamental forces of nature [2] were born, and most of the original material had annihilated itself. One billionth of a second after the Big Bang, the Universe contained both subatomic particles and antiparticles. When particles of matter and antimatter come into contact, they destroy one another and release vast amounts of energy. Fortunately, there were more particles than antiparticles – 1,000,000,001 particles for every 1,000,000,000 antiparticles. Within an instant, the mutual annihilation of matter and antimatter had reduced the material in the Universe to a fraction (1/200,000,000) of its original content.

After this rapid start, it took another 300,000 years before the Universe cooled sufficiently for hydrogen and helium nuclei to capture free electrons and form their atomic structure. Until then, electrons colliding with photons had made the Universe opaque. However, once the electrons became bound to atoms, photons could travel unimpeded, making the Universe transparent. It was made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium – three-quarters hydrogen, one-quarter helium and trace amounts of lithium and beryllium. The other elements we know today, like carbon and oxygen, would not exist for another 200 million years.

Throughout the Universe, the initial distribution of hydrogen and helium was not homogeneous – it was clumpy. Over millions of years, gravity shaped these clumps into vast nebulae – clouds of gas where stars would one day be born. As gravity continued pulling material in the cloud ever closer, dense cores began forming at the nebulae's centre. These cores were extremely hot because of the immense gravitational pressure but were not yet hot enough to make a star – instead, they were protostars. Surrounding these protostars, a swirling disk of gas known as an accretion disk fed the growing core, fuelling its eventual transformation. As the protostar became denser and hotter, the temperature at its core eventually reached a critical point, triggering nuclear fusion and marking the star's birth.

Figure 1‑1:The Big Bang timeline.

Two hundred million years after the Big Bang, star formation was happening all over the Universe. Unlike modern stars, these ancient stars, known as Population III stars, were made entirely of hydrogen and helium. Other than trace amounts of lithium and beryllium left over from the Big Bang, the remaining elements did not yet exist.

This lack of heavy elements resulted in Population III stars being extremely massive – hundreds of times more massive than the Sun. And because of their size, the lives of these first-generation stars were relatively short, typically a few million years.

This comparatively short lifespan is due to the relationship between a star's mass and how quickly it consumes its fuel. Massive stars like Population III stars burn through their nuclear fuel much faster than smaller stars. In their cores, hydrogen atoms fuse into helium, releasing vast amounts of energy. Bigger stars have much higher core temperatures and pressures, accelerating this fusion process and causing them to exhaust their fuel rapidly. This fast fuel consumption leads to lifespans of only a few million years for these early, massive stars. In contrast, smaller stars, such as our Sun, burn their fuel more slowly and live for billions of years.

The immense size of these first-generation stars meant they lived fast and died young. After millions of years of fusing hydrogen to helium – a process known as hydrogen burning – these early stars began to run out of fuel. When this happens, the outward radiation pressure from the fusion process can no longer counteract the gravitational force of the outer layers, and the star begins to collapse inwards. As it collapses, the density increases, raising the temperature until it becomes so hot that unburnt hydrogen in the star's shell ignites. Radiation pressure from the revitalised hydrogen-burning process prevents further collapse and causes the star's outer layer to expand, transforming it into a Red Supergiant.

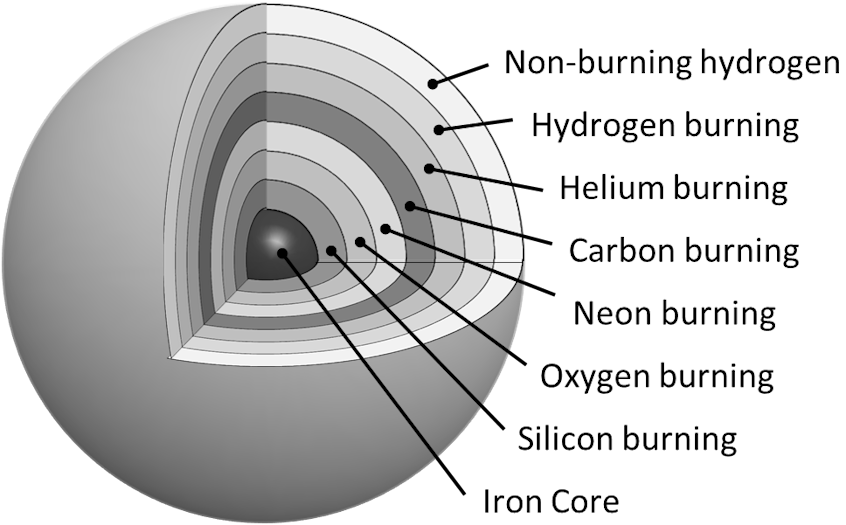

When the hydrogen-burning shell is exhausted, the star collapses again. Under immense gravitational pressure, the core becomes hot enough to fuse helium into heavier elements, specifically carbon and oxygen, in a helium-burning phase. This helium-burning phase is short-lived compared to hydrogen burning but crucial for producing the elements needed for later stages.

As helium burning runs out, gravitational collapse again intensifies, heating the core further. The core temperature rises to a point where carbon burning begins, forming elements like neon, sodium, and magnesium. Each subsequent burning stage progresses more quickly as higher temperatures are required to initiate fusion, but less energy is released than in prior stages. When carbon is depleted, the star collapses again, and oxygen burning begins, yielding silicon, sulphur, phosphorus, and magnesium.

When oxygen is exhausted, the star collapses yet again, and silicon burning occurs, producing elements such as iron, nickel, and cobalt. The cycle of fuel exhaustion, gravitational collapse, and nuclear fusion (see Figure 1‑2) manufactures every element in the periodic table up to iron, atomic number twenty-six. Beyond iron, the fusion process no longer releases energy but instead requires it, and so the process stops at this point.

Figure 1‑2: The onion-like fusion layers of a high-mass star near the end of its life.

When the synthesis of iron is complete, the star dims and begins its final collapse. It collapses in seconds, crushing the atoms in the core to unimaginable densities. What happens next depends on the star's mass.

Most Population III stars have a mass so immense that they collapse into a black hole, and the elements they created are lost to the Universe forever. For less massive stars, the enormous amount of energy generated by its collapse causes the star to explode in a blaze of glory. In the super-hot plasma of the supernova explosion, there is, for a brief second, enough heat and energy to create elements heavier than iron. Some of these stars also collapse into a black hole, and most of the newly created elements disappear into a black hole. However, for a brief second, before the black hole forms, a small amount of metal-rich [3] material is ejected into the surrounding space, laying the foundations for a new generation of stars.

But not all early stars ended up as black holes. The least massive Population III stars (still massive compared with more recent Population I and II) ended their lives by collapsing into neutron stars after the supernova explosion. These objects, made almost entirely of neutrons, are so incredibly dense that the extreme pressure crushes ordinary atoms into neutrons, and a teaspoon of the material would weigh more than five billion tonnes. Like their slightly larger siblings, these Population III stars eject some of the elements they synthesised during their life into the interstellar medium, making new material available for the next generation of stars.

|

Mass Range |

Collapse Type |

Remnant |

Fate of Synthesised Elements |

|

>140 |

Direct Collapse (no supernova) |

Black Hole |

Minimal or no ejection; most material collapses into a black hole |

|

40–140 |

Supernova |

Black Hole |

Ejected into the surrounding space before black hole formation |

|

10–40 |

Supernova |

Neutron Star |

Ejected into the surrounding space |

Table 1‑1: The fate of Population III stars when their fuel supply is exhausted. High-mass Population III stars collapse directly into a black hole, and their synthesised elements are lost to the Universe forever. However, for Population III stars with a mass of less than 140 solar masses, the elements they created during their lives are ejected into the surrounding space when they die, making new material for the next generation of stars – Population II stars.

With the availability of heavy elements from supernova explosions, the next generation of stars, Population II stars, are smaller than their predecessors. Heavier elements allow nuclear fusion in less massive stars, and smaller stars consume their fuel more slowly. Hence, Population II stars have lifespans of about ten billion years, compared to the few million years their massive Population III predecessors.

Less massive stars also have less traumatic endings, with only a few large enough to form black holes. So, when they finally die, the elements they have manufactured are not lost in a black hole but are scattered throughout the Universe. Population II stars manufacture and distribute every stable chemical element in the periodic table during their burning, or more spectacular supernova, stages.

The youngest stars of all are Population I stars. These stars are less than ten billion years old and benefit from the metal-enriched remains of previous stellar generations. The Sun is a typical Population I star, approximately five billion years old and currently in the middle of its stable hydrogen-burning phase, known as the main sequence. This phase will last for roughly another five billion years until the Sun depletes the hydrogen in its core. As the hydrogen runs out, the Sun will enter a new evolutionary stage and expand into a Red Giant, with hydrogen fusion continuing in a shell surrounding its inert core.

During this Red Giant phase, the Sun's outer layers will cool and expand dramatically, causing it to swell up to a size large enough to engulf the inner planets, potentially including Earth. Eventually, the hydrogen-burning shell will exhaust its fuel. The Sun's core will then contract further under the force of gravity, increasing pressure and temperature to the point where helium can briefly fuse into carbon in a process known as a helium flash. But, unlike more massive stars, the Sun has insufficient material to sustain proper helium burning for more than a few seconds. In this final burp of life, energy generated by the helium flash will blow away half the Sun's mass, creating a planetary nebula [4] and leaving a small, dense core called a white dwarf. This white dwarf will be an Earth-sized relic of the Sun, containing most of its original mass compressed into a small volume and marking the final stage of its stellar life.

White dwarfs have no energy source because all fusion reactions have ceased, but they shine brighter than at any other stage in their lives because they are still intensely hot. Eventually, the white dwarf will cool and become a cold black dwarf. However, since the time for a white dwarf to lose all its heat is estimated to be one million billion years, which is longer than the current age of the Universe, black dwarfs do not yet exist.

The nebula created from the Sun's dying throes will eventually disperse throughout interstellar space, returning metal-enriched elements to the galaxy. Some of this material will join with gas and dust from other nebulae to form a new star one day. Some may even form planets. Ultimately, some may sow the seeds of new life. To paraphrase Carl Sagan, we are all just stardust.

[1] Quarks are so small that if you ate one it wouldn't taste of anything. However, physicists refer to different types of quarks by their flavours. Six flavours exist - up, down, top, bottom, strange and charm. Strange indeed!

[2] Gravity, the weak nuclear force, the strong nuclear force, and electromagnetism.

[3] Astronomers refer to all elements other than hydrogen and helium as metals.

[4] Planetary nebulae are unrelated to planets. The name originates from early observations that suggested they were planets in the process of forming. This is now known to be incorrect and the nebula is in fact material from a star’s death throes.