Key Figures from Baked Alaska

We often hear that recent temperatures are the highest since records began. However, this statement refers only to written records, which span just a few centuries — an instant in geological time. If we step beyond human history and look at the natural archives of Earth’s past — locked within ice cores, deep-sea sediments, and ancient rocks — a very different picture emerges.

For much of Earth’s history, global temperatures have been far higher than today. The same is true for carbon dioxide levels and sea levels, which have fluctuated dramatically over millions of years. There have been periods when CO2 concentrations dwarfed modern values, when vast inland seas covered continents, and when polar ice was nowhere to be found. Oxygen levels, too, have seen major shifts, shaping life and the environment in ways we can only begin to appreciate.

The key message is this: climate is not static. It never has been, and it never will be. Change is the rule, not the exception, driven by forces far older and more powerful than human activity — tectonics, orbital cycles, and the evolution of life itself. The graphs below provide a glimpse into this ever-changing past, offering the perspective that is often missing from today’s discussions on climate.

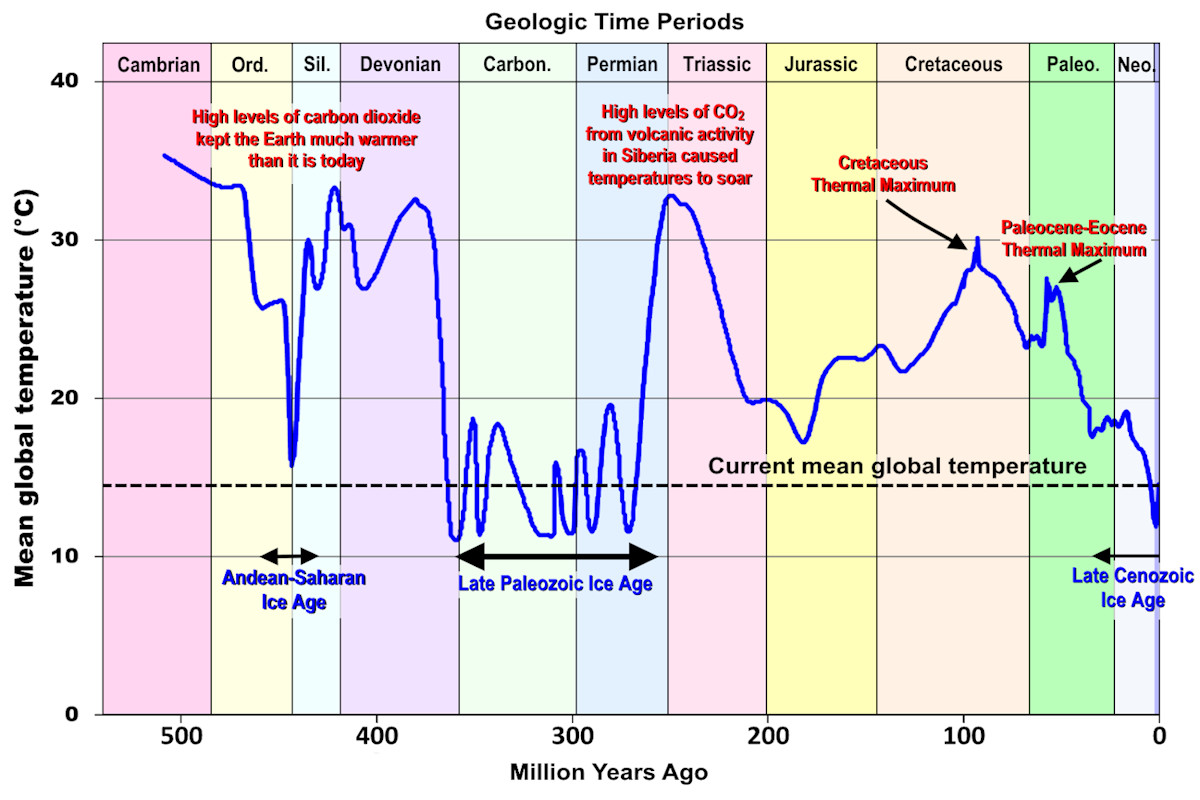

Phanerozoic temperatures

During the Phanerozoic Eon (which spans from approximately 541 million years ago to the present), evidence from natural archives such as ice cores and rock sediments indicates that, for most of this period, Earth's average temperature was significantly warmer than it is today — just as it has been throughout its entire 4.5-billion-year history. [Data from The Smithsonian Institution]

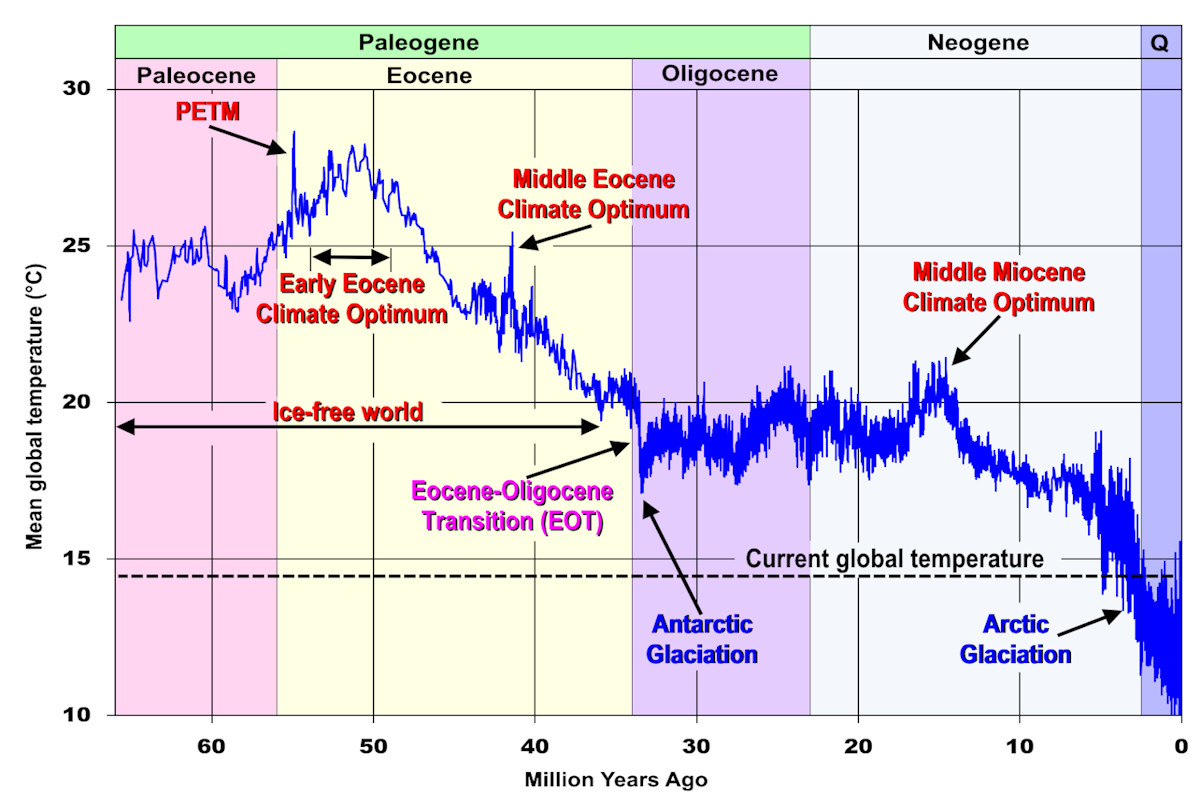

Cenozoic temperatures

Global temperatures throughout the Cenozoic have shifted from an early greenhouse world to the ice age cycles of the present. The era began with intense warmth, peaking during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum and the early Eocene, when ice-free poles and expanded tropics characterised the planet. A long cooling trend followed, accelerating in the Oligocene with the first major Antarctic glaciation. After a brief warming during the Miocene Climatic Optimum, temperatures continued to decline, leading to the expansion of Northern Hemisphere ice sheets and the Quaternary glacial cycles. The Holocene, our current interglacial, remains warm but far cooler than the peak of the early Cenozoic. [Data from Zachos et al.(2008) and Hansen et al.(2013)]

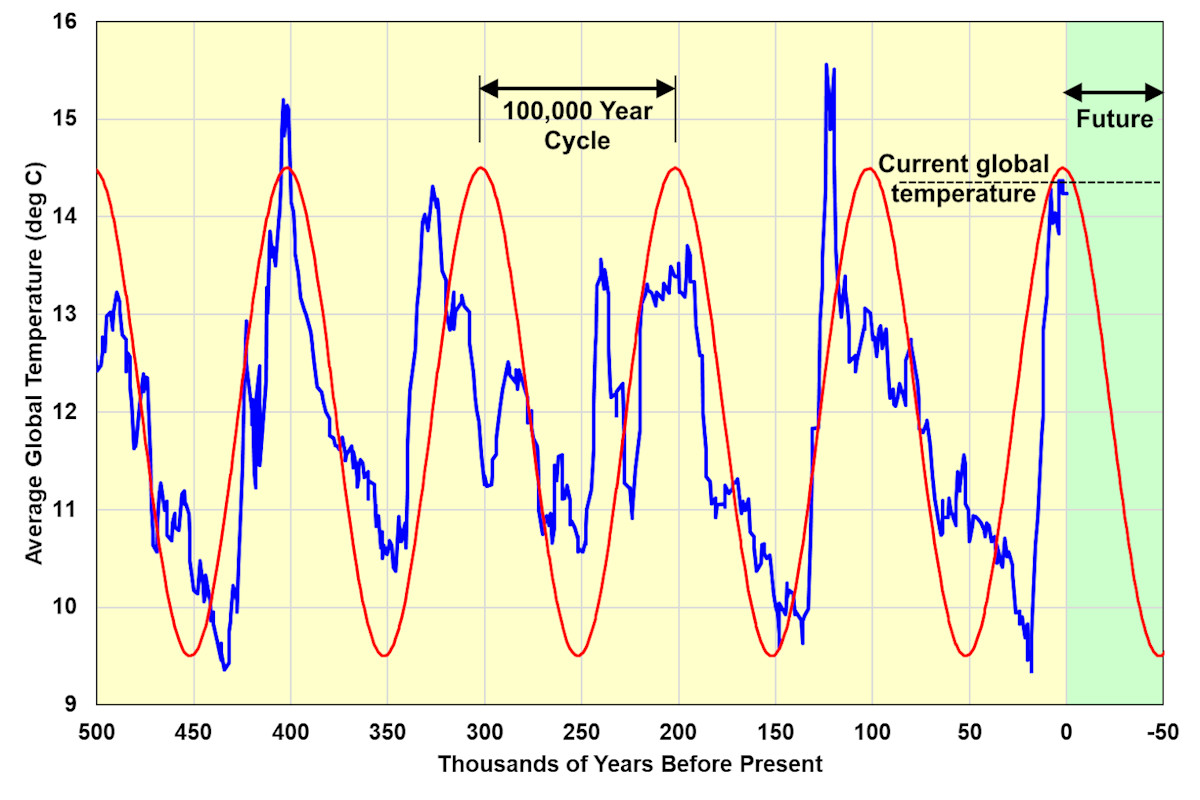

Milankovitch Temperature Cycles

Global temperatures have cycled between warm interglacials and cold glacial periods for much of the Quaternary, but over the past 500,000 years, these cycles have followed a dominant 100,000-year pattern closely linked to Milankovitch cycles. These orbital variations influence the amount of solar energy reaching Earth, driving long-term climate changes. The graph shows a repeating pattern of gradual cooling into glacial maxima, where ice sheets expanded and temperatures dropped, followed by more rapid warming into interglacials, such as the Last Interglacial (~125,000 years ago) and the present Holocene. These cycles are part of a longer trend of climate fluctuations that have shaped Earth's environment over millions of years. [Temperature data from J. Hansen et al. (2013)]

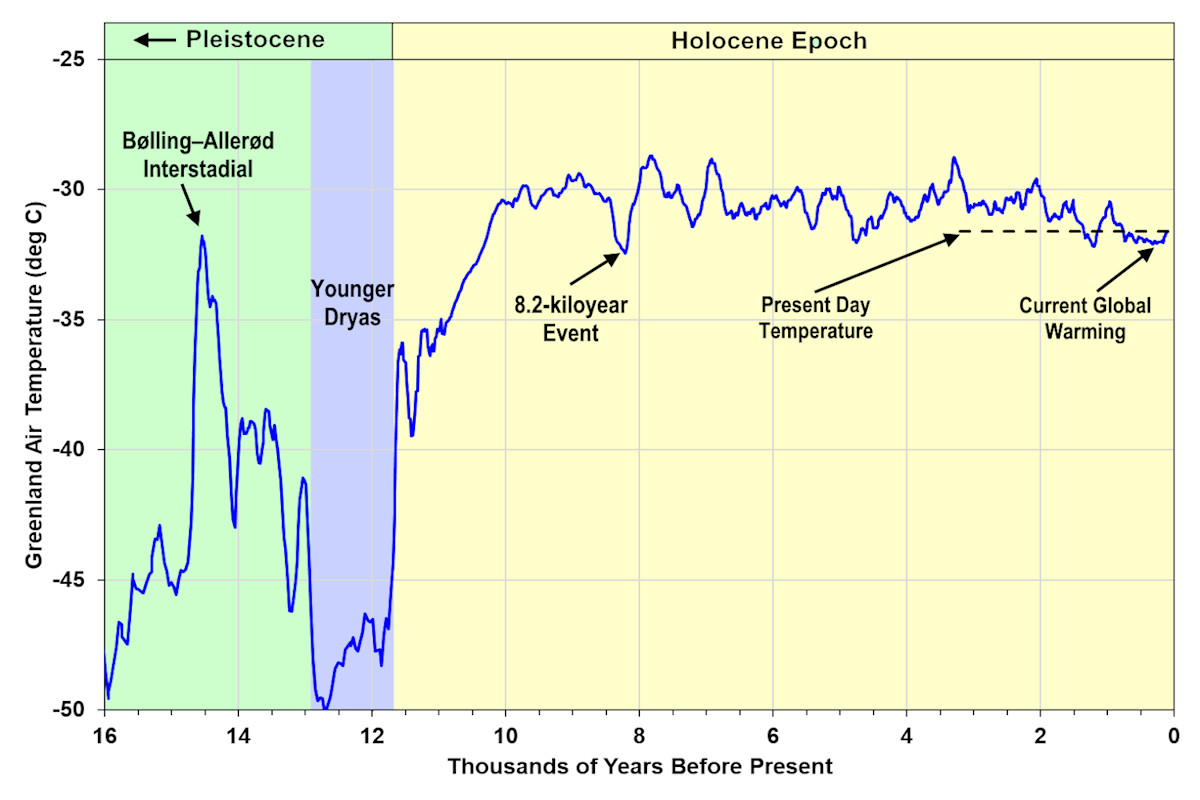

Greenland Ice Core Data

The Greenland temperature record over the past 16,000 years reveals significant climate shifts. Around 14,700 years ago, rapid warming during the Bølling–Allerød Interstadial marked the retreat of ice sheets, but this was interrupted by the Younger Dryas (~12,900 years ago), a sudden return to near-glacial conditions likely caused by disruptions in ocean circulation. Warming resumed with the onset of the Holocene (~11,700 years ago), though the 8.2-kiloyear event brought a brief cooling, linked to the sudden drainage of glacial lakes. Temperatures remained high for much of the Holocene but have gradually declined over the past few thousand years, with present -day values lower than most of the Holocene warm period. [Data from GISP2]

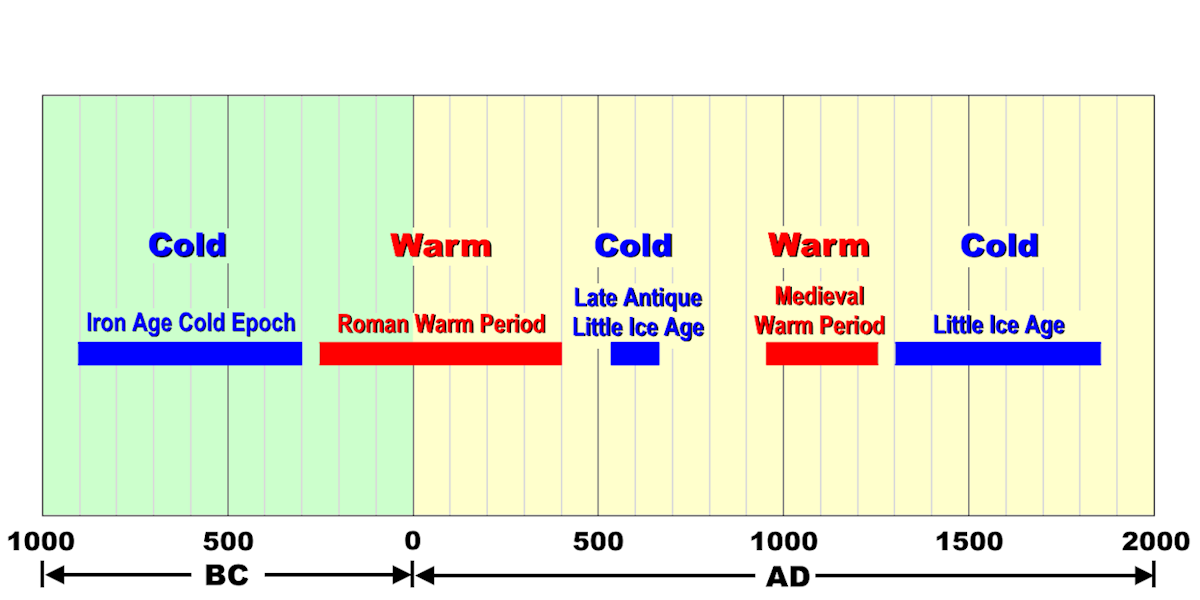

Recent Climatic Events

The timeline illustrates the continuous shifts between warm and cold periods throughout history, reinforcing that climate has never been stable. The Iron Age Cold Epoch brought a period of cooling before temperatures rose during the Roman Warm Period, which coincided with the expansion of ancient civilizations. This warmth was interrupted by the Late Antique Little Ice Age, a time of significant cooling likely influenced by volcanic activity and weakened solar output. The climate then rebounded with the Medieval Warm Period, a phase of relative warmth that supported population growth and agricultural expansion. This was followed by the Little Ice Age, a prolonged period of colder conditions that brought harsher winters and environmental challenges. These recurring fluctuations highlight the natural variability of climate over different timescales.

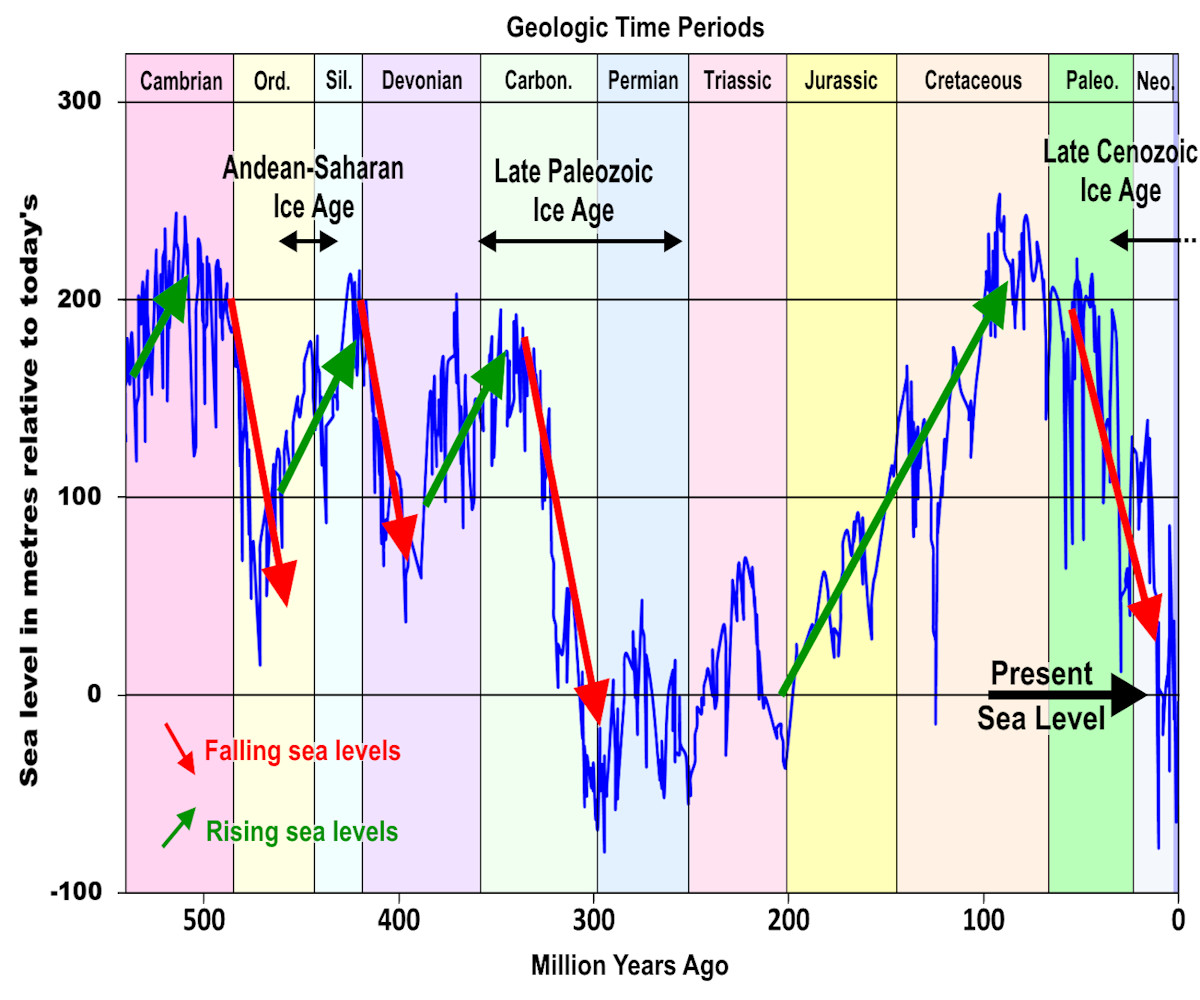

Phanerozoic sea levels

A plot of global sea-level fluctuations produced by Exxon researchers shows falls during the Late Paleozoic and Late Cenozoic Ice Ages, but a rise during the Andean-Saharan Ice Age. The falls are explained by glacial eustasy: large ice sheets formed on polar continents, locking up water and lowering sea levels. In contrast, the Andean-Saharan glaciation was less extensive and occurred during a time of active tectonics. Continental breakup and subsidence created new ocean basins and expanded marine shelf areas, increasing ocean volume and raising sea levels despite glaciation. Thus, while glaciation typically lowers sea levels, tectonic factors can override this effect under certain conditions. [Exxon Corporation (Haq et al. 1987, Ross & Ross 1987, 1988)]

Phanerozoic carbon dioxide levels

GEOCARB III shows that atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were much higher than today for most of the Phanerozoic Eon. CO₂ peaked during the Cambrian and Ordovician, declined through the Devonian and Carboniferous, and reached a low during the Permian–Triassic. After rising again in the Mesozoic, levels fell through the Cenozoic to near-modern values. These long-term trends reflect a balance between volcanic outgassing and CO₂ drawdown via silicate weathering, organic carbon burial, and the uplift of mountain ranges that enhanced chemical weathering. Major ice ages occurred during periods of low CO₂, highlighting the link between atmospheric carbon dioxide and global climate. [Data from GEOCARB III (Berner & Kothavala (2001)]

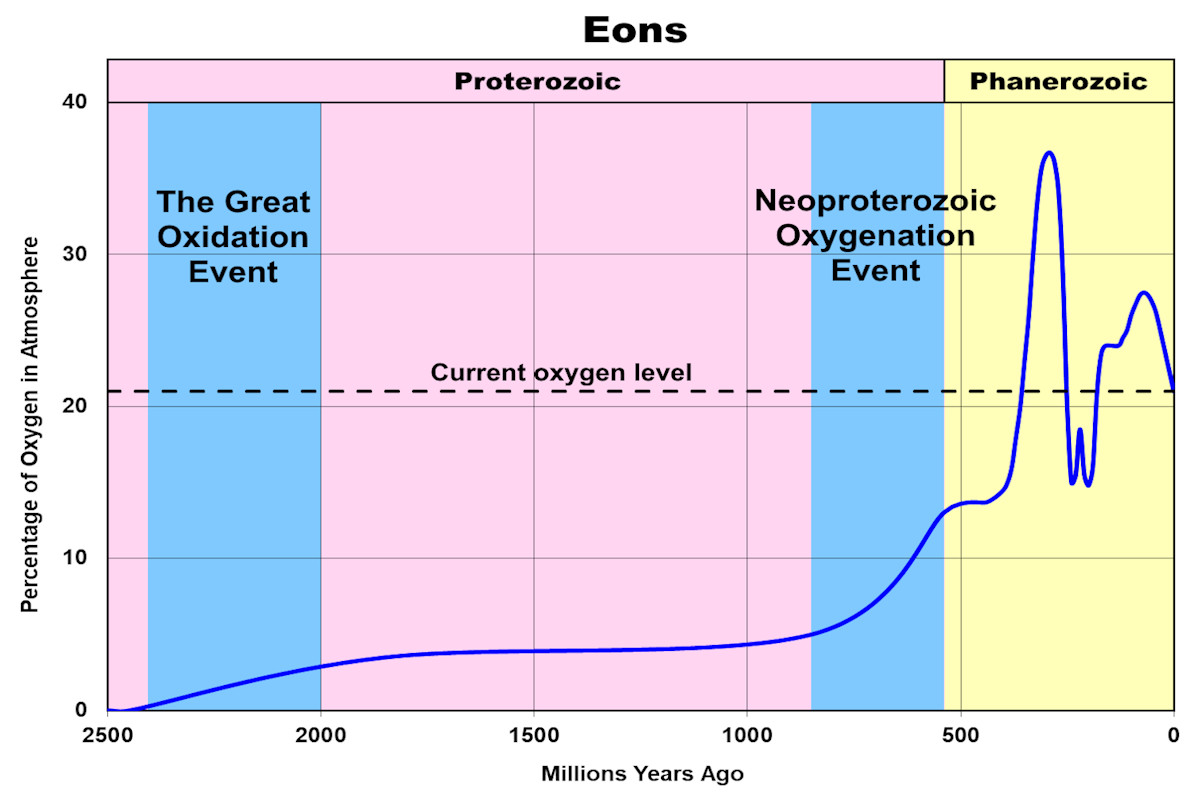

Oxygenation of Earth's Atmosphere

This graph shows the long-term rise of atmospheric oxygen. For the first half of Earth’s history, oxygen levels were negligible. The first major increase — the Great Oxidation Event — occurred around 2.4 billion years ago, when oxygen produced by photosynthetic cyanobacteria began to accumulate in the atmosphere. Oxygen remained low for over a billion years, a period known as the Boring Billion, until the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event (c. 800–540 Ma), when levels rose again, likely driven by tectonic activity, nutrient influx, and the burial of organic carbon. This oxygenation paved the way for complex multicellular life in the Ediacaran and Cambrian periods. [Data from Heinrich D. Holland's "The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans"]

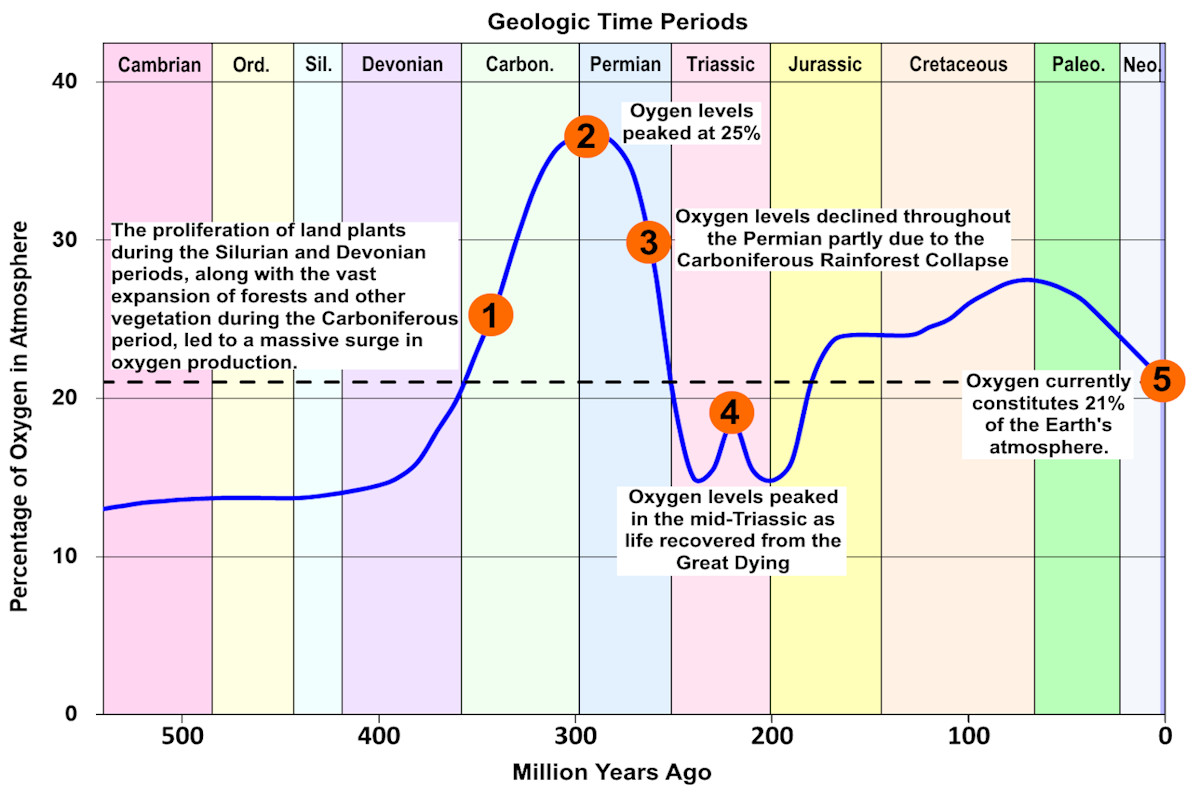

Phanerozoic oxygen levels

This graph focuses on oxygen levels over the past 540 million years. Oxygen peaked during the Carboniferous and early Permian, reaching levels much higher than today — conditions that supported giant arthropods and widespread coal-forming forests. These high levels were driven by the burial of vast amounts of organic matter. Oxygen then declined in the late Permian and fluctuated through the Mesozoic and Cenozoic. Drops in oxygen have been linked to mass extinction events, while periods of high oxygen often coincided with evolutionary radiations, highlighting its importance in shaping life on Earth.

It is interesting to note that if oxygen levels were less than 15%, fires would not burn, yet at greater than 25% oxygen, even wet organic matter would burn freely.