Chapter 3

The Oxygen Catastrophe

Five hundred million years after the Earth's formation, high levels of greenhouse gases from volcanic activity made the atmosphere warmer than it would have otherwise been. However, during this period, the Sun was cooler than it is today, which helped counteract the warming caused by the greenhouse effect. The net result was an atmosphere with temperatures much hotter than today but sufficiently cold to allow liquid water. But this was an inhospitable place. Giant active volcanoes with bubbling vents of hot toxic gases dominated the landscape. The oceans were hot, steamy, green-coloured, and highly saline concoctions that lacked oxygen. The atmosphere also lacked oxygen and would have been lethal to humans had we existed. There was little sunlight, frequent lightning storms, and with no protective ozone layer, dangerous levels of ultraviolet radiation.

Despite these conditions, some believe it was about this time, four billion years ago, that the first forms of life emerged. However, this was the time of the Late Heavy Bombardment when meteorites, up to ten kilometres across, pelted the Earth. The relentless barrage of debris remaining from the formation of the planets would make life almost impossible at this time and for the following 200 million years.

Life most likely emerged after the Late Heavy Bombardment at the start of the Archean Eon 3.8 billion years ago. How it began remains uncertain. However, studies have established the basic and essential characteristics necessary for life.

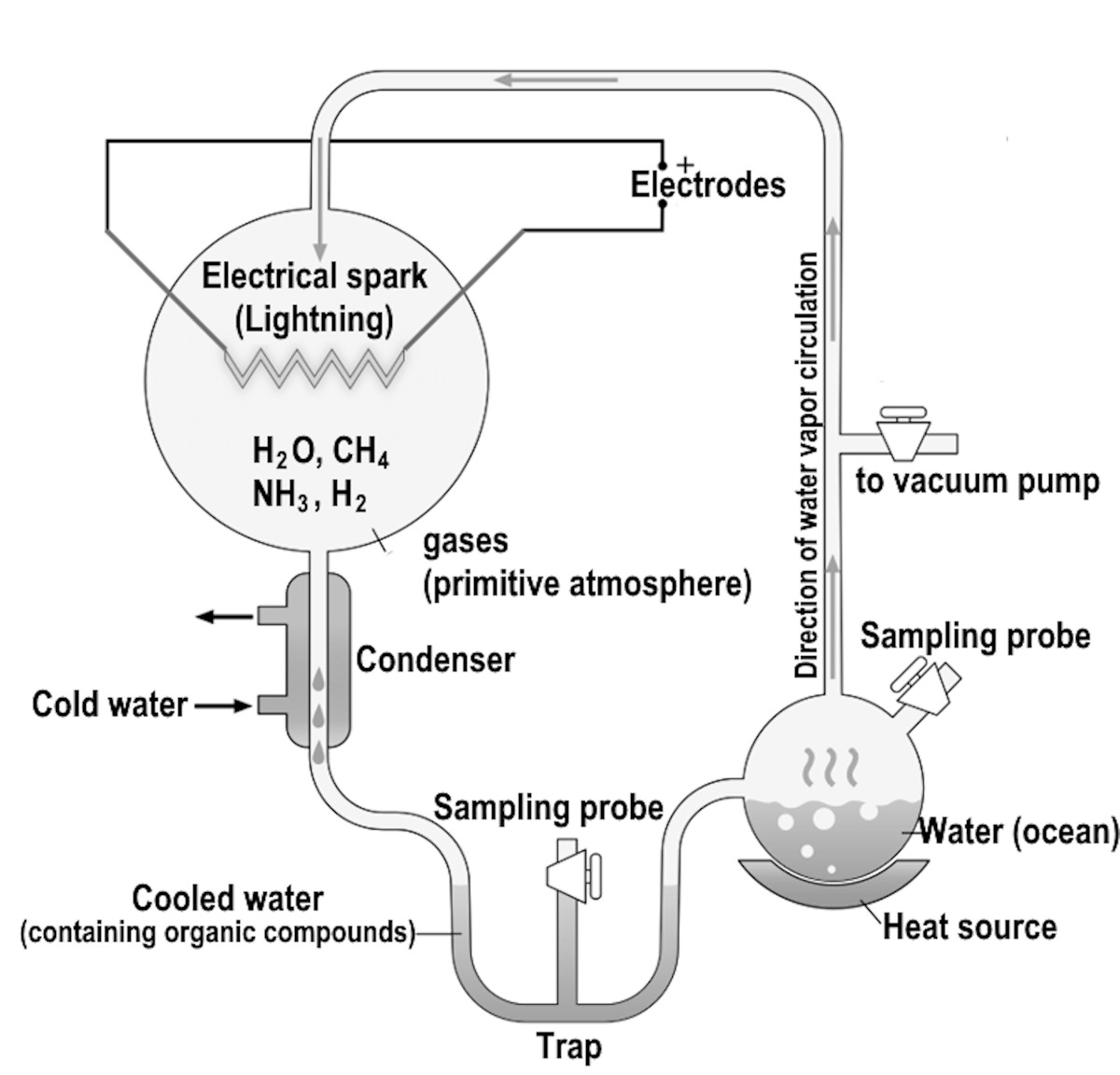

In a well-known experiment, Stanley Miller, working in Harold Urey's laboratory at the University of Chicago in 1953, created amino acids, the building blocks of life, from conditions resembling those on early Earth. Miller used two flasks connected by a glass tube. In one flask, water simulated the oceans, while the second contained a mix of methane, ammonia, and hydrogen to represent the early atmosphere. Next, he heated the first flask containing water to simulate the evaporation and subsequent condensation in the early Earth's atmosphere. Finally, Miller inserted two electrodes to create sparks and simulate lightning in the gaseous mix. After running the experiment for several days, Miller observed that amino acids, crucial in making proteins, had formed in the flask representing the oceans.

Figure 3‑2: Miller-Urey experiment.

Critics say that the primordial soup created by the Miller-Urey experiment wasn't rich enough to produce today's complex life. However, later analyses of additional samples created by Miller in his original experiment showed a far richer and more diverse mix of amino acids than first reported. Miller, who stored and catalogued the samples but never analysed them, added hydrogen sulphide to his original gas mix. Hydrogen sulphide, which smells like rotten eggs and causes the smell produced by stink bombs, is released by volcanoes and was present in large amounts in the primordial atmosphere. Perhaps this smelly gas was responsible for the beginning of life on Earth.

While the exact mechanisms remain uncertain, the origin of life on Earth likely involved a combination of chemical processes that transformed simple inorganic molecules into complex organic compounds. These compounds eventually developed the ability to replicate and carry out metabolic functions, leading to the earliest forms of life – single-celled microorganisms called archaea.

These organisms, which are still around today, can live in the most extreme environments, earning them the nickname "extremophiles". The earliest archaea lived in the anoxic oceans of the time and had a chemotrophic lifestyle, getting energy from chemical reactions rather than sunlight. Some derived their nourishment by converting simple molecules, such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen, into methane. Other archaea metabolised sulphur-rich compounds found near underwater volcanic vents, even though temperatures near these vents could reach hundreds of degrees centigrade. For a while, Earth's first inhabitants ruled alone in the harsh, anoxic world of the Archean Eon, but it wasn't too long before another type of organism emerged.

These new organisms, known today as cyanobacteria, significantly altered the planet's environment, paving the way for the development of complex life. Cyanobacteria are a group of photosynthetic bacteria often referred to as blue-green algae due to their colour and aquatic habitats, although they are not true algae. They are among Earth's oldest known life forms, with fossil records dating back over 3.5 billion years. Their emergence marked a pivotal moment in Earth's history because they introduced oxygen into an atmosphere previously devoid of it.

During the Archean Eon, Earth's surface vastly differed from today's landscape. The planet was dominated by vast oceans rich in dissolved minerals such as iron and silica. The atmosphere lacked free oxygen and was composed mainly of methane, ammonia, and other gases that would be toxic to most modern life forms. In this primordial soup, cyanobacteria thrived, colonising shallow coastal regions where sunlight could penetrate the water column. They formed slimy microbial mats on the seafloor, utilising sunlight for energy and contributing to the early biosphere.

These microbial mats were not just passive layers; they actively trapped and bound sediment particles from the surrounding water. As sediment accumulated, new generations of cyanobacteria grew on top of the older layers, continuing the cycle of growth and sediment trapping. Over centuries and millennia, this process led to the formation of structures resembling giant mushrooms, known as stromatolites. Stromatolites are layered sedimentary formations created by the lithification – or hardening – of these microbial mats, with a living mat of bacteria growing on the surface. They provide some of the most ancient fossil evidence of life on Earth and offer valuable insights into early life and environmental conditions.

Figure 3‑2: What a scene from the Archean Eon may have looked like. Stromatolites (in the foreground), active volcanoes, frequent lightning storms, and a moon that appeared much more prominent than today [Imagen 3].

While stromatolites were much more common in ancient times, they are relatively rare today due to changes in environmental conditions and competition from other organisms. However, they can still be found in hot springs in Yellowstone National Park, USA, in the Bahamas, and most famously, in Shark Bay, Australia.

But the mats of cyanobacteria did more than merely build stromatolites. As a by-product of their metabolism, they produced oxygen through photosynthesis. Unlike the archaea, which thrived without sunlight, cyanobacteria used sunlight as their primary energy source. Through photosynthesis, they converted sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates to use as food, releasing oxygen as a waste product. This seemingly simple process profoundly impacted the Earth's atmosphere and the future of life on the planet. In a previously oxygen-free world, the Earth's methane-rich atmosphere was irrevocably changed by the gradual accumulation of oxygen produced by cyanobacteria.

Initially, the iron-rich seas absorbed the oxygen, turning the green anoxic waters red with rust. Over time, oxidised iron settled on the seafloor, creating layers of red mineral deposits. Eventually, there was no more iron to oxidise, and oxygen began entering the environment for the first time in Earth's history. But these early bacteria were anaerobic, and to them, oxygen was poisonous. Killed by their own waste products, cyanobacteria numbers decreased, and the seas returned to their previous unoxygenated state. Silica and dead bacteria replaced iron oxide on the seafloor, creating layers of shales and silica-rich cherts. A few cyanobacteria survived the oxygen poisoning and eventually thrived again. Then, as before, rusty iron filled the oceans, and once again, oxygen killed the cyanobacteria. This cycle continued until the cyanobacteria eventually learnt to live in an oxygenated environment.

The alternating bands of iron oxide and silica sediment laid down billions of years ago are visible today in Banded Iron Formations (Figure 3‑3). Layer upon layer of red iron ore separated by grey chert shows that aerobic cyanobacteria took more than a billion years to evolve into oxygen-tolerant organisms. Once the cyanobacteria learnt to survive in an oxygenated environment, they flourished, and when the oceans could no longer soak up their bacterial excrement, free oxygen began entering the atmosphere. Each bacterium could only release a minute amount of oxygen, but the combined output of billions of cyanobacteria over millions of years raised the oxygen concentration to deadly heights. Although only a fraction of today's levels, there was enough oxygen to kill most anaerobic life.

Figure 3‑3: Banded Iron Formation with alternating bands of iron-rich deposits and cherts. [Graeme Churchard]

Known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE), this oxygen accumulation triggered Earth's first mass extinction. For the anaerobic organisms that had evolved in an oxygen-free world, the rising oxygen levels were fatal. Oxygen is a very reactive molecule that can create free radicals and other reactive forms. These reactive forms can damage cell structures like DNA, proteins, and fats, causing the cell to die.

Only organisms that could hide or mutate survived the GOE. Those who hid, did so in mudflats and swamps where the oxygen couldn't reach. The survivors, whose descendants are still living today, are the bacteria that produce pungent smells from bogs and decompose dead matter. Organisms that couldn't hide died of starvation or had their innards spilt into the polluted waters. Oxygen changed the anaerobes' food supply, making it inedible. Those who didn't starve died when oxygen attacked and dissolved their cell membranes. Eventually, the extinction subsided, and the planet was no longer oxygen-free.

The Great Oxidation Event lasted approximately 400 million years, from 2.4 billion years to 2 billion years ago. When it ended, the seas were no longer anoxic and atmospheric oxygen had risen from practically zero to roughly ten per cent of today's levels. It is estimated that up to 99 per cent of all life on Earth perished in a mass extinction event more extensive than any other in Earth's history.

Today, we still live with the threat that oxygen will kill us just as it did the anaerobes two billion years ago. Oxygen remains toxic to all cells. It creates free radicals, which damage cell structures. Like all aerobic life, we only exist because our bodies produce enzymes that change free radicals into something less toxic. These antioxidants continuously battle against free radicals, but unfortunately, many will lose the battle. Free radicals cause ageing and contribute to many forms of cancer. They contribute to alcohol-induced liver damage, Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and Alzheimer's and play a role in many more diseases and illnesses.

While the increase in oxygen was catastrophic for anaerobic organisms, it opened new ecological niches for organisms capable of utilising oxygen for metabolic processes. Aerobic respiration is more efficient than anaerobic pathways, allowing organisms to extract more energy from nutrients. This increased energy availability facilitated the evolution of more complex, multicellular life forms.

The rise in oxygen levels also led to the formation of the ozone layer, which shielded the Earth's surface from harmful ultraviolet radiation. The Great Oxidation Event led to a world that could eventually support the diversity of life we know today.

Yet, this transformation came at a terrible cost. The oxygen-rich environment, essential for the emergence of complex life forms, simultaneously triggered one of Earth's most devastating mass extinctions and contributed to Earth's first climatic catastrophe – the Huronian ice age.